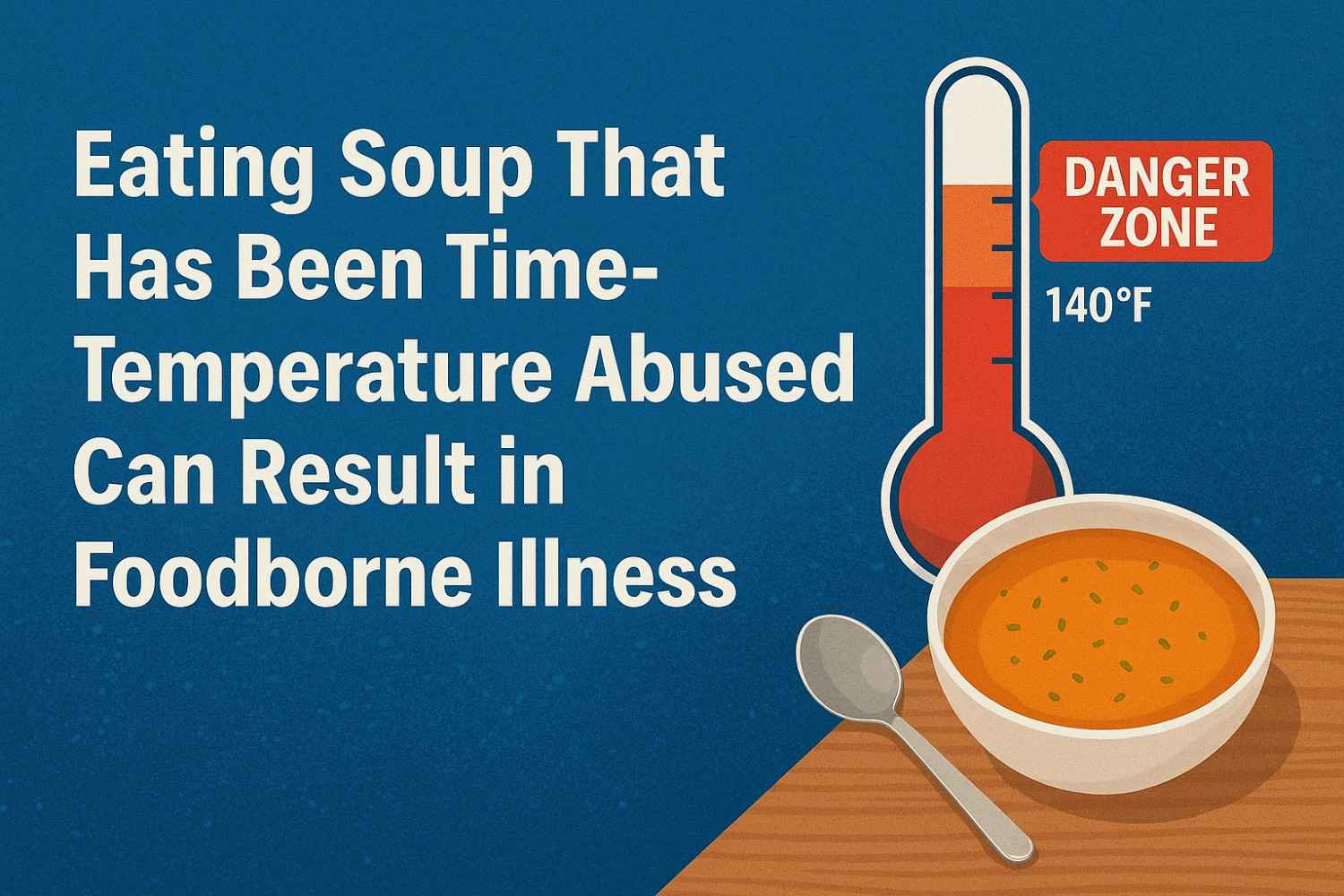

When eating soup that has been time-temperature abused can result in foodborne illness, it’s not just a classroom warning from a food-safety course—it’s a reality that affects home cooks and professional kitchens alike. Soups are among the most comforting foods, but they can also become one of the most dangerous when temperature control fails.

In simple terms, time-temperature abuse happens when food stays too long in the temperature danger zone, the range between 40 °F and 140 °F (4 °C – 60 °C) where harmful bacteria multiply most rapidly. When a pot of soup is left out to cool on the counter or held at a lukewarm serving temperature, conditions become ideal for bacterial growth.

Even if you later reheat that soup to a boil, it may no longer be safe. Certain bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus, produce toxins that survive cooking heat and continue to cause illness. Understanding how this happens—and how to stop it—is the key to protecting yourself, your family, and your customers.

What Does “Time-Temperature Abuse” Mean for Soup?

Time-temperature abuse occurs any time food spends more than four total hours in the danger zone. Soups are especially risky because they’re high in moisture, rich in nutrients, and often cooked or cooled in large volumes that trap heat.

Once soup falls below 135 °F or rises above 41 °F without control, bacteria begin multiplying exponentially. If you later refrigerate or reheat that same batch, you might only destroy live bacteria, not the toxins they left behind.

Common Bacteria That Thrive in Abused Soup

Bacillus cereus

This organism flourishes in cooked foods such as rice, meat, and soups left at room temperature for extended periods. It produces toxins that lead to nausea, vomiting, and stomach cramps, usually within hours of consumption.

Clostridium perfringens

Often called the “cafeteria germ,” this bacterium grows quickly in bulk foods like soups, gravies, and stews that cool slowly. It causes diarrhea and abdominal pain, typically developing 6–24 hours after eating.

Staphylococcus aureus

This bacteria commonly enters food from improper handling—like touching ready-to-eat soup with bare hands. It creates heat-resistant toxins that trigger vomiting and nausea, even after reheating.

When these pathogens find the right conditions, the soup effectively becomes a breeding ground that even boiling temperatures can’t completely fix.

Symptoms of Foodborne Illness From Soup

The signs of illness depend on which microbe caused the problem, but most foodborne infections share a few unmistakable red flags:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Watery or severe diarrhea

- Abdominal cramps and pain

- Fever or chills

- General weakness and dehydration

Symptoms can appear within hours or up to several days after eating contaminated soup. In mild cases, recovery happens naturally, but in vulnerable populations—such as children, pregnant women, or older adults—complications can become serious.

Why Improper Cooling and Holding Are High-Risk

Slow Cooling = Rapid Growth

A deep pot of soup cools slowly because heat escapes gradually from the center. If it takes longer than two hours to drop below 70 °F, bacteria can multiply to unsafe levels long before refrigeration.

Hot Holding Mistakes

Many people keep soup warm on low burners or buffet lines, unaware that temperatures often hover under 135 °F. Once that threshold is crossed, the “danger clock” begins ticking.

Reheating Isn’t a Cure

Bringing soup to a boil later might kill active bacteria but can’t remove toxins produced earlier. That’s why prevention—not reheating—is the only truly safe solution.

How to Prevent Time-Temperature Abuse in Soup

1. Keep It Hot or Cold

- Hot soups must be kept at 140 °F (60 °C) or higher.

- Cold soups, such as gazpacho, should be stored at 40 °F (4 °C) or lower.

- Use thermometers, not guesswork, to verify temperatures.

2. Follow the Two-Hour Rule

Never leave perishable food out of temperature control for more than two hours. When ambient temperature exceeds 90 °F (32 °C)—for example, during outdoor service—limit exposure to one hour.

3. Cool Rapidly and Safely

To prevent lingering in the danger zone:

- Divide large batches into smaller, shallow containers.

- Use ice baths or cooling paddles while stirring frequently.

- Follow the two-stage cooling process:

- 135 °F → 70 °F within 2 hours

- 70 °F → 41 °F within the next 4 hours

4. Store and Reheat Properly

- Refrigerate cooled soup immediately, uncovered until below 41 °F, then cover tightly.

- Reheat leftovers to 165 °F (74 °C) for at least 15 seconds before serving.

- Reheat only once—avoid mixing fresh and old soup in the same pot.

5. Practice Good Hygiene

Always wash hands, sanitize ladles, and avoid direct hand contact with ready-to-eat items. Even the cleanest kitchen can’t compensate for cross-contamination from handlers.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How long can soup safely sit out before refrigeration?

Soup can stay unrefrigerated for up to two hours. If the room temperature is above 90 °F, that limit drops to one hour. Beyond that, bacteria grow too quickly for the food to remain safe.

2. Can boiling soup again make it safe after it’s been left out?

No. While boiling kills many bacteria, it doesn’t destroy heat-resistant toxins already produced by Bacillus cereus or Staphylococcus aureus. Once contaminated, the soup should be discarded.

3. How can I tell if soup has gone bad after cooling?

Look for sour odors, off-colors, or curdled textures. However, some contaminated soups show no visible signs, which is why time-temperature tracking is more reliable than smell alone.

4. What’s the best way to cool soup quickly for storage?

Place the pot in an ice-water bath, stir frequently, or transfer to small, shallow containers. This increases surface area and helps the soup pass through the danger zone faster.

Conclusion: Safe Soup Starts With Smart Temperature Control

In short, eating soup that has been time-temperature abused can result in foodborne illness, but every one of these risks is preventable. By keeping foods out of the danger zone, cooling and reheating correctly, and practicing good hygiene, you can enjoy hearty soups without worry.

A thermometer, a clock, and careful habits are your best defenses against invisible hazards. Remember—when in doubt, throw it out. It’s far better to lose a batch of soup than risk a night of food poisoning.